My Biography

A Little about Who I Am

As you search for the surgeon that's just right for you, it's extremely important to closely evaluate their credentials. People suffering from obesity are some of the highest risk patients to operate on. The co-morbidities of obesity are some of the highest risk conditions known to medicine. A small surgical mishap can kill a patient who suffers from obesity. Make your selection very carefully when choosing a Bariatric Surgeon.

Once you've found a top-notch technician, you've done half your work toward finding the right surgeon. You must now look a little closer to see what makes them who they are. There is a slowly growing number of good doctors out there, who can adequately perform the surgery itself, but this type of operation isn't like having your gallbladder removed… where the surgeon does a slick removal and the process is over. Even a perfect gastric bypass can be unsuccessful for the patient if the education and follow-up with the doctor is inadequate (or in some cases, wholly absent). Gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy and gastric banding surgery require a life-long commitment to many lifestyle changes. You will be teaming up with your surgeon for the years to come, so the strength of the relationship you have with your surgeon is one of the most crucial factors that determines a successful outcome.

| “ The most common question that people ask me is 'What made you go into this sort of surgery? ” | |

The most common question that people ask me is “What made you go into this sort of surgery?” The ones who don't know me well yet are really asking me “What does a skinny woman like you know about how obesity feels?” (One delightfully forthright woman actually admitted that this is what she thought when she first laid eyes on me at a lecture... Once she heard my lecture and got to know me, she had her answer. Bless her for being honest.)

If you're looking for a doctor who you will see before your operation, but is too important to take your calls or see you after surgery, who stands at the door of your hospital room to talk at you, who isn't an active part of your care after surgery or who dumps you onto a dietician to take care of you after surgery… then I'm not for you. There are plenty of those out there, so you won't have trouble finding them.

My style is not for everyone. It's very personal, it's very hands-on …and it's very successful. I hold my patient's hands, I sit on the bed next to them in the hospital, I take my own calls and I take my patient's outcomes very personally. If you aren't prepared to participate actively, honestly and directly with me, then I suggest that you look elsewhere for your surgeon.

At the request of many of you, I will try to answer the above question and maybe a few others. I do want you to know that this wasn't the easiest thing to write, nor is it the easiest thing for my family to read. But every day I ask my patients to be totally honest with me and I think that the least I can do is take off my white coat for a minute and be totally honest with you.

The influence of a small Nebraska town…

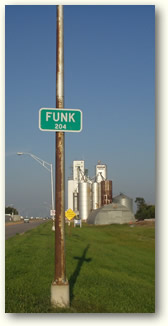

I grew up in Funk, Nebraska, a tiny little town which is about 100 miles from anywhere. The sign at the edge of town boasted a population of 150, but due to a small but significant population boom over the last 20 years, they reported a blistering 204 at last headcount. They even had to change the sign.

My upbringing was fairly typical under the circumstances. As there were no other girls my age, I was a tomboy. I didn't think it unusual to enjoy biking, swimming in the infamous Funk Lagoon and various irrigation ditches, chasing cows with motorcycles and shooting at unfortunate feathered creatures with BB guns (forgive me). I also engineered, in a highly specialized corner of the garage, the delivery of emergency medical care to the small animals that my cat would deliver to the back step. Well, I admit that the last one isn't so typical.

My upbringing was fairly typical under the circumstances. As there were no other girls my age, I was a tomboy. I didn't think it unusual to enjoy biking, swimming in the infamous Funk Lagoon and various irrigation ditches, chasing cows with motorcycles and shooting at unfortunate feathered creatures with BB guns (forgive me). I also engineered, in a highly specialized corner of the garage, the delivery of emergency medical care to the small animals that my cat would deliver to the back step. Well, I admit that the last one isn't so typical.

I always excelled in sports, right along with the boys who were my best friends. In looking back, I recognize now that it was due to a combination of acquired discipline from organized sports and inherited (and “community acquired”) discipline from generations of hard working farmers that I learned how to put my head down and work until the job is finished, no matter how tediously difficult the road is and no matter who told me that I couldn't do it. My family is mostly of German stock, with an unbelievably, almost oppressively, strong work ethic… and a particular affection for homemade sausage. Like my grandmother, the best way to motivate me to do anything was (and is) to tell me that I couldn't. It is unfortunate that there was a fair amount of that. My first grade teacher told me that I had to be a nurse, not a doctor, because I was a girl. That was the tip of the iceberg.

| “ People always ask me why I chose obesity surgery as a career. ” | |

Why did I choose obesity surgery as a career? Sometimes these “obvious” questions don't have obvious answers. It has taken some soul searching on my behalf, and not all of it pleasant, to arrive at an honest and insightful answer. That's why I mentioned above that there was a fair amount of people telling me that I couldn't do this or that, but in truth, it goes much deeper than that.

My seemingly idyllic childhood had dark undercurrents of not fitting in. I just never did quite fit the mold of what my social and peer community expected of me. I never wanted to stay in Nebraska, marry a farmer and have a dozen kids to run the farm. I spent most of my childhood plotting my escape from the stereotypes and dreaming of “getting out”. I was the only girl in my class until high school and I didn't enjoy normal “girl” pastimes and cliques. When I entered junior high, it wasn't acceptable for me to spend all my time with the boys with whom I had grown up, so I became somewhat estranged from my circle of friends. Funk didn't have a high school, so I had to go off to another school in 9th grade where I found that I just couldn't fit in to the expected small-town girl stereotype. I did the best I could to excel in the things that I was good at – sports and academics. This didn't endear me to my female peers, however, and my teen years were peppered with esteem shattering encounters with bullies. My aspirations just weren't the same as those of my peer group and I couldn't wait to "get out."

|

My “support” system crumbled as I was repeatedly told that it was my own fault that I didn't “blend” and that I should make a better effort to fit in. I didn't know what it was to "fit in."

I felt that in spite of everything, I was headed in the right direction and if I could just stick it out long enough, I would eventually escape and it would all be okay. I moved forward, but I never completely shook off the intimate knowledge of what it was like to feel like an outcast.... to be sidelined because of who I was and what I wanted. I was a very successful athlete and student with many older friends, and even before I put high school behind me I was looking toward a (hopefully) bright future which, believe me, couldn't come quickly enough. But even though I knew I had much potential for further success, it was the kind of success that wasn't encouraged for a Midwestern girl, and my peers judged me a failure… only because I didn't meet their expectations.

Any person suffering from obesity knows how society treats those who don't fit in. It hardly seems to matter what you have to offer from a personal or academic standpoint, because society only sees someone who doesn't fit the mold... a failure. This type of treatment stays with a person for their entire life. It can devastate and permanently scar an otherwise strong human being. It can destroy self esteem and bruise a person's potential. Or, in some of us lucky ones, we find that we can “own the pain” and thusly be able to recognize it in others. We can use this insight as a positive part of our lives and to make a positive impact on others.

| “ I believe that 'not fitting in' during my childhood gives me great insight as a Bariatric surgeon. ” | |

In retrospect, I'm sure that it was because of having felt like I did throughout my childhood that I always rooted for the underdog and intervened on behalf of those who were being trampled upon. (Believe me, I landed in hot water more than once during my surgical residency as a result of my attempts to protect younger residents from rampant abuse.) At any rate, having grown up in a family devastated by obesity, I have firsthand knowledge of the fear and pain that every day brings to an obese person. I have hard-earned insight about what it feels like to have much to contribute and still not be “accepted.” So in the end, I didn't have to listen very hard to hear my calling. As I stated on the home-page, there's NO segment of our population that is more misunderstood and mistreated than those suffering with obesity, and medical care for the obese needs to start with human insight.

I found outstanding role models in very small towns .

I've now shared the history behind my decision to be a surgeon, but how I learned to put it all into action came from an outstanding role model – a surgeon by the name of Dr. Doolittle. He was a local surgeon in Holdrege, Nebraska, a town near Funk, and the only surgeon in the area. Having known from the time I was 4 that I wanted to be a doctor, and by my teens that I wanted to be a surgeon, I was keen to just “get on with it,” and Dr. Doolittle was a huge part of that.

I've now shared the history behind my decision to be a surgeon, but how I learned to put it all into action came from an outstanding role model – a surgeon by the name of Dr. Doolittle. He was a local surgeon in Holdrege, Nebraska, a town near Funk, and the only surgeon in the area. Having known from the time I was 4 that I wanted to be a doctor, and by my teens that I wanted to be a surgeon, I was keen to just “get on with it,” and Dr. Doolittle was a huge part of that.

Dr. Doolittle was a young surgeon whom I met through my mother, who was a nurse. He took me under his wing and allowed me to tag along with him as he operated in little towns all over south-central Nebraska. He was a sensitive, kind, caring doctor who communicated from his heart. He is truly the epitome of the ideal country surgeon, respected not only for his technical work, but for who he is and how he connects with his patients. He taught me how to share warmth and compassion while maintaining a patient's confidence in the medical care that I'm providing. And he's still one of the best surgeons I've ever met.

| “ I am uniquely fortunate to have been trained by both the Grandfather of Bariatric Surgery AND the pioneers of the Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass. ” | |

In later years, one of the bright spots of my surgical residency was training under Dr. Edward Mason, at the University of Iowa Hospital in Iowa City, Iowa. Dr. Mason is considered to be the Grandfather of Bariatric Surgery, having performed the world's first Gastric Bypass - at the University of Iowa in 1966. He is the founder of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery and the very first meetings were held at my old hospital. Working directly with Dr. Mason was an honor for the generations of surgeons who had the pleasure of doing so. He was tracking obesity and obesity related syndromes through generations decades before others gave it athought. He is both a phenomenal technician and a true gentleman. In addition to teaching me techniques of operating on the morbidly obese which were years ahead of his time, he was a master of physical diagnosis, teaching me the importance of examining and really listening to the patients, not just reading the charts and X-rays. He is a pioneer of obesity surgery in general and the gastric bypass specifically. I am extremely fortunate to have been in the last group that was trained by the Grandfather of Bariatric Surgery as well as the first surgeon to be taken into the practice of the pioneers of the Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass. There is no one else in the world who can say that.

| “ I believe that you can't learn to be empathic; you have to genuinely feel it as a part of who you are. ” | |

When I was 18, I spent some time working in a funeral home, hoping to learn more about human anatomy, etc. I got much more than I bargained for because what I ended up doing was not only helping with autopsies and eye enucleations (eye removal for donation), but assisting people in making funeral arrangements. I quickly found that once I got past the shyness and awkwardness of being a stranger, I could just give simple comfort to someone who was in need, and I enjoyed that feeling.

My patients frequently tell me that they feel like I understand what they’re going through, when they wouldn’t have thought, at first glance of me, that I would have a clue. Well, I’m glad that all of that angst that I felt while I was growing up really did turn positive in my life. When I look into my patient’s eyes and see pain, they can look into mine and see that I “get it”. I need to have this kind of understanding with a patient in order to feel confident in moving forward together to surgery.